If you have been diagnosed with prostate cancer, the important thing to remember is that you’re not alone. Many men have had a high degree of success with treating prostate cancer and you have every reason to expect that you will return to a normal, healthy life.

What is Cancer?

Cancer of the Prostate

Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer

Further Tests After Diagnosis

Clinical Stages of Prostate Cancer

What is Cancer?

The billions of cells that make up the human body grow and divide, with old constantly being replaced by new. Sometimes, cells reproduce in an uncontrolled, unstructured way and grow into a lump or tumour.

There are two kinds of tumours: non-cancerous (benign) and cancerous (malignant). Benign tumours do not spread to other parts of the body and are rarely life threatening, however, malignant (cancerous) tumours can attack nearby cells and destroy them.

The cancer cells can also get into body fluids and spread to other parts of the body. This is called a secondary cancer or metastases.

Cancer of the Prostate

In New Zealand, prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men, most often developing in men over 65 and rarely occurring in men younger than 55.

About one in 13 men will develop prostate cancer before the age of 75 and in very elderly men; prostate cancer often grows very slowly and may cause no symptoms.

Some men are more at risk of developing prostate cancer than others, but age is a major factor, as is a family history of prostate cancer – the more first-degree relatives with prostate cancer, the higher a man’s risk of developing the disease.

It is not clear what causes prostate cancer. However, male hormones, especially testosterone, stimulate the growth of cancer cells in the prostate but the speed at which prostate cancer grows varies from man to man.

Prostate cancer is often difficult to detect as it may not cause symptoms and may be too small for a doctor to feel during a routine rectal exam.

With a slow-growing prostate cancer, a man may live for many years without symptoms.

If the cancer grows too much, however, the prostate usually squeezes the urethra, which it surrounds. Symptoms may then start, such as difficulty in passing urine. As the same symptoms can be caused by other problems, difficulty passing urine does not always mean that prostate cancer is present.

Read about other prostate problems here.

Cancer in the prostate can affect cells near the prostate, and also spread, to other parts of the body, or the blood. Symptoms still may not be obvious during the early stages of the cancer spread (metastasis).

Find out more about the stages of prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer tends to spread to lymph nodes, bones (especially ribs and bones around the hip and lower back), liver, lungs and rectum. Cancer cells that have spread to other parts of the body will also grow, causing other symptoms.

Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer

The doctor will need to determine for certain that your symptoms are caused by prostate cancer and may do the following tests in the process of your diagnosis:

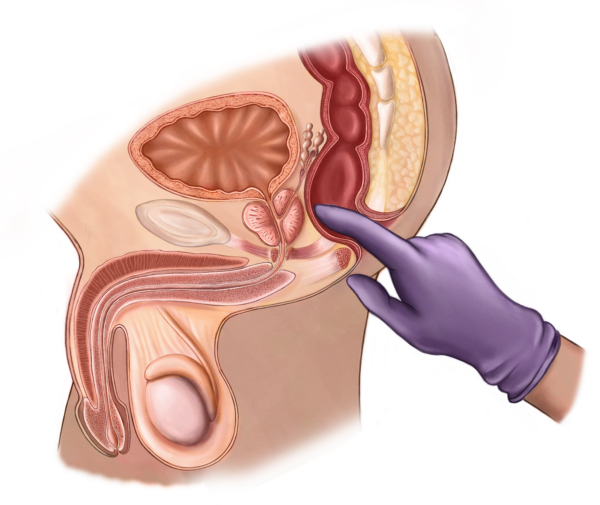

Rectal exam

The doctor wears a rubber glove and inserts a finger into the anus to feel the prostate through the wall of the rectum. This is called a ‘digital rectal examination’ or DRE. The doctor checks the size, shape and hardness of the prostate.

Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA)

A blood test for PSA is usually performed in addition to DRE in the process of detecting prostate cancer. The test measures the level of PSA, a small protein produced by the prostate, in the bloodstream.

If the amount of PSA in the blood is above normal levels, it may be due to an enlarged prostate, prostatitis or prostate cancer. If the PSA level is high, it is more likely to be due to prostate cancer. However, results from a PSA test alone cannot confirm whether prostate cancer is present.

Blood levels of PSA can be measured by very sensitive laboratory tests. PSA levels usually increase with age, but the normal range of PSA in the blood is up to about four micrograms per litre.

Conditions affecting the prostate which cause PSA blood levels to rise include:

- BPH

- Prostatitis (infection of the prostate)

- Biopsy (removal of very small pieces of prostate tissue using a fine needle)

- A catheter placed into the urethra

- Prostate Cancer

The results of your PSA test

If cancer is present, the blood level of PSA and how much it changes over the months can tell the doctor whether the cancer is growing or staying the same. However, PSA levels cannot predict the precise stage of the cancer.

For example, very occasionally some men with cancer confined to the prostate may have high PSA levels while men with more advanced prostate cancer may have normal PSA levels.

Monitoring your PSA levels

Doctors have different opinions about the importance of PSA tests and how they are best used in the detection and monitoring of prostate cancer. Your doctor will advise you on how often you should have a PSA test, as each patient and their circumstances are different.

Biopsy

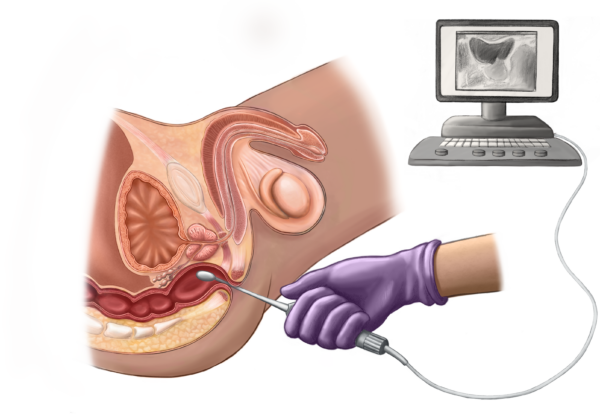

A biopsy is the removal of very small pieces of prostate tissue using a fine needle. A local anaesthetic may be given first, but most patients say the discomfort is mild.

The tissue is then looked at under a microscope to see if cancer cells are present. A biopsy is the only way to show for certain whether or not prostate cancer is present.

Some doctors will take a picture of the prostate with an ultrasound probe before they do a biopsy. This will guide the biopsy.

Further Tests After Diagnosis

If cancer is found, the doctor will need to do more tests to ascertain the size and extent of the spread (if any) of the cancer. Not all men with need to undergo imaging tests as the risk of spread to other organs can be estimated by PSA levels and cancer grade.

Tests may include the following:

Chest X-ray examination

A standard chest X-ray examination can be used to see if the cancer has spread to the lungs.

Total body bone scan

A bone scan can show whether the cancer has spread to the bone. In a total body scan, a very small amount of radioactivity is injected (with no significant risk) and produces a picture of the bones. If cancer is present in the bones, it will often show up on the scan.

CT scanning (Computerised Tomography)

This painless technique uses computer technology to produce an X-ray picture of the prostate and nearby organs.

Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA)

A PSA test can tell the doctor how quickly the cancer is growing, or if it is stable.

Lymph node biopsy

To help identify the extent of prostate cancer, lymph nodes near the prostate may be removed during surgery to remove the prostate.

Microscopic spread of cancer cells cannot always be detected by X-ray examinations, scans or clinical examination. However, the level of PSA and grade of the cancer can often predict the risk of microscopic spread.

Clinical Stages of Prostate Cancer

Once prostate cancer has been diagnosed by a biopsy, the doctor will determine the extent of the cancer using a staging system. Staging the cancer indicates the size of the tumour, the possible involvement of the lymph nodes and spread of the cancer.

Gleason Score

Because often several different tumor patterns are seen, the most common tumor pattern is assigned a score from 1 to 5 and the second most common pattern is assigned a score, using the same scale. The two scores are added together to give a Gleason Score, ranging between 2 and 10. Scores of 2 to 6 identifies mildly aggressive prostate cancer, 7 moderately aggressive and scores of 8 to 10 are highly aggressive cancers.

TNM System

Another commonly used staging system is the TNM System, which stands for:

- Tumour (indicates the size or involvement of a malignant tumour)

- Node (indicates whether lymph nodes have cancer cells in them)

- Metastasis (indicates whether cancer has spread to other parts of the body)

The stages are called T1, T2, T3 and T4, N0 and N1, and M0 and M1.

Your doctor can tell you more about staging and its importance in selecting treatment options.

Tumour Confined to the Prostate

Low risk of metastases

Stage T1

The tumour is confined to the prostate gland and cannot be felt during a rectal exam. At this stage, the tumour is not likely to cause symptoms. During treatments for BPH, prostatitis or other problems, tumours in this stage will often be found by chance.

Common treatments:

Your doctor may recommend radical surgery or radiation therapy. No treatment may be a sensible option in some circumstances. Instead of surgery or radiation therapy, the size and activity of the cancer is monitored by your doctor during regular rectal exams and PSA tests. Treatment may then be started when, and if, needed. Find out more about watchful waiting.

Tumour Confined to the Prostate

Medium risk of metastases

Stage T2

The tumour is confined to the prostate but is large enough to be felt during a rectal exam. There are often no symptoms.

Common treatments:

Radical surgery and/or radiation therapy. Depending on the patient’s age and health, watchful waiting may be the best option.

Tumour Spread Outside the Prostate

High risk of metastases

Stage T3

The tumour has spread to tissues touching, or adjacent to, the prostate. The glands that produce semen (seminal vesicles) may have cancer in them. Difficulty passing urine is a common symptom.

Tumour Spread Outside the Prostate

Very high risk of metastases

Stage T4

In Stage T4, the tumour has spread to organs near the prostate, such as the bladder, rectum or the side wall of the pelvis. Bone pain, weight loss and tiredness are common symptoms.

Common treatments:

Simple surgery to improve passing of urine (a transurethral resection of the prostate or TURP), or hormone therapy may be used.

Patients usually have symptoms at this stage, and treatment is required.

Further stages:

Stage N0 – There is no evidence that lymph nodes have cancer cells in them.

Stage N1 – One of more lymph nodes have cancer cells in them.

Stage M0 – There is no evidence that cancer has spread into distant parts of the body.

Stage M1 – The cancer has spread (metastasised) into distant parts of the body.

Read about the possible treatment options for prostate cancer.